by: Ellen C. Caldwell

for JSTOR Daily

Last March, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a free-speech appeal which was filed after a handful of high school students were prohibited from wearing American flag t-shirts to school on Cinco de Mayo.

Commenting upon the notoriety of the case, reporter David G. Savage noted that although schools have restricted insensitive student clothing in the past, this case “drew greater attention because an American flag was considered the provocative message.”

One might wonder how wearing an American flag could be problematic. As Clayton A. Hurd’s 2008 case study demonstrates, the celebration of Mexican holidays at one school heightened existing racial tensions after a white student touted the American flag on his face and in his hands while making disparaging remarks to his classmates of Mexican-descent. In both cases—Hurd’s and the one brought to Supreme Court—white students were disciplined after using the U.S. flag as a symbolic weapon to assert their “American-ness” (or, more generally, whiteness) in order to intimidate and provoke students of Mexican descent.

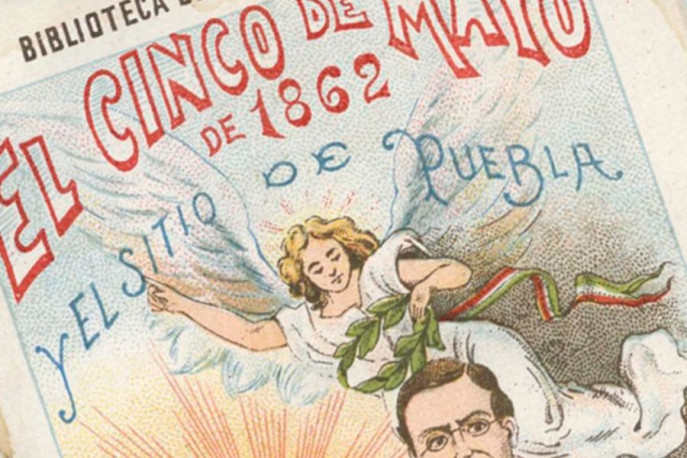

Hurd explores the exclusion and violence that many Mexican-descent students experienced at Hillside High, particularly as related to the school-wide celebration ofCinco de Mayo (commemorating the Battle of Puebla Day which led to Napoleon’s 1862 defeat) and Dieciséis de Septiembre (celebrating Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1810). Hurd describes Hillside as a bimodal school on California’s central coast with about half white and half Mexican-descent students. Prior to mandatory, schoolwide celebrations of these holidays, Hillside High had taken the “cultural consumption approach” to celebrating Cinco de Mayo. This approach often features entertainment and Americanized Mexican food. (Daniel Enrique Pérez explores such white commodification and appropriation of Cinco de Mayo beautifully in this poem.)…